PP 625 in the Collection was published by NIANIS, the research section of the Peoples of the North Institute (A.K.A. Herzen Institute), an education organization that completed the Unified Northern Alphabet to serve as the basis for languages of other indigenous populations in the USSR.

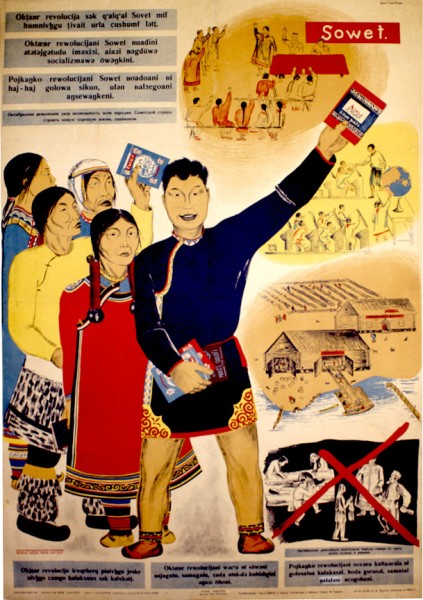

This image shows a poster in Nanai language. In 1932, a Nanai alphabet was derived from the primer, Sikun pokto, (New Life) and the man on this poster holds that book in his hand. The second book in the background raised behind the man is Cuz Dif (New Word). Cuz Dif was a primer in Nivkh language, spoken in Outer Manchuria and on the northern half of Sakhalin Island.

Many people of the Northern USSR and Siberia had no written language until 1932. The NIANIS institute was the only link researchers had to these indigenous populations and their staff directed the first textbooks, political literature and propaganda written in a myriad of Northern languages. Production of the works was in partnership with the Prosveshchenie (Enlightenment) Publishing House of Leningrad.