Youth

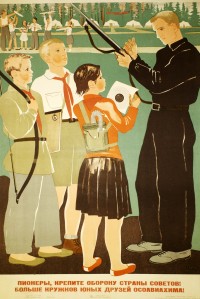

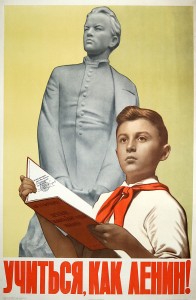

From the moment the Bolsheviks became a ruling party, they sought to nurture future generations. In 1918, they founded the Young Communist League (Komsomol) for young adults. In 1922, the Pioneer organization for children was established. Both programs instilled values appropriate to the revolutionary epoch. Yet this youth-centered policy faced challenges. The chaos of World War I, the Russian Civil War, famines, and privation left 4.5 million youth (in 1921) without shelters or guardians. While the state provided homes, many young victims roamed in criminal gangs. [Text continues at bottom of page]

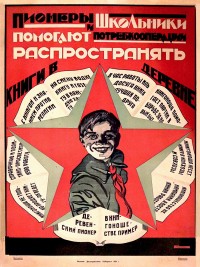

As the New Economic Policy (NEP) brought social stability, the People's Commissariat of Education experimented with radical and progressive forms of instruction. Simultaneously, the commissariat initiated a long-term campaign against adult illiteracy, enlisting youth in the endeavor.

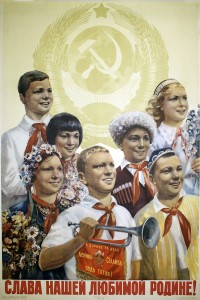

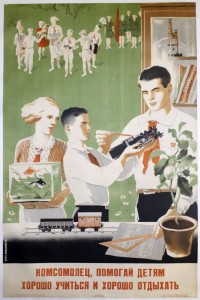

During the Russian Civil War, idealists had joined the Komsomol to serve in the Red Army and perform other pressing missions, developing an archetype based on self-sacrifice and a rough, masculine culture. The Komsomol was meant to steer the next generation toward communism and away from the temptations of society. Despite having 2 million members by 1927, a figure encompassing one-half of working class youth but only 6 percent of youth of peasant origins, the organization was not reaching enough young people. From 1928 onward, the Komsomol called on its traditions of militancy as a way to place a new direction on the organization and attract particular segments of youngsters. Readily joining the party's drive to industrialize the country, it sent members to the most important economic projects and government campaigns, including the violent collectivization of the countryside.

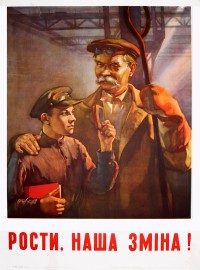

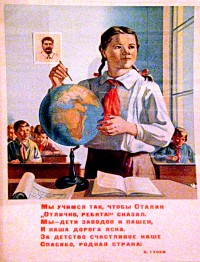

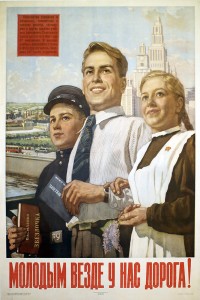

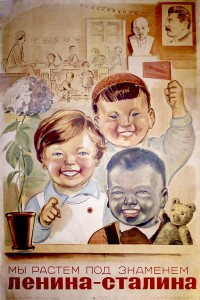

By the mid 1930s, education policy began to favor traditional forms by curbing the experimental methods of the 1920s. Through government-organized spectator sports, youth learned about health, well-being and comradeship, at the same time, national physical education programs were joined by paramilitary training curricula. Propaganda in the 1930s and 1940s exalted Stalin for having provided a happy, fruitful childhood. Although some families suffered political repression in the grim years of the Great Terror under Stalin, many youths nonetheless benefited from the system during that same period, emerging as a generation better fed, more educated, and more committed to communism than their predecessors. Even the looming war with Germany did not disrupt rigorous study and training for future triumphs. Those who had earned their stripes in the industrialization campaigns or emerged from the state-run education system formed the backbone of the war effort. The exploits of young people in the war, both at the battlefront and home front, set them apart from future generations.

Curricular conservatism was strictly re-imposed after the war. Having isolated boys and girls in separate classrooms, authorities furthered conventional curricular standards at odds with the co-ed classes and educational innovation of the 1920s. The ideal envisioned a neat, obedient, well-disciplined youth growing into a loyal member of a society under siege. Yet the resulting program reflected authorities' fears of a postwar generation gap just as much as it defined actual everyday life. Youth too young to have served in the war seemed alien to those even a few years older. Although comprised of a select clique of children born to the party elites, the stilyagi, or "style hounds," provoked a moral panic. Not only did they challenge societal norms, they also aped the fashions of Western movie stars by acquiring brightly colored dresses and zoot suits, and by developing a distinctive slang. While they represented only a tiny minority, they were the first of several postwar countercultures, which later included poets, dissidents, and rock-n'-rollers.

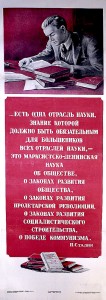

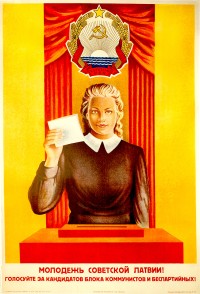

Official youth culture was slightly liberated under Premier Nikita Khrushchev. Educational reforms scrapped some repressive, conservative aspects of late Stalin-era practice. Yet Khrushchev introduced required manual and vocational training for all, even those bound for higher education, born of fear that elite youth in the land of the proletariat did not value physical labor. From the late 1950s, the Soviet Union cautiously opened its doors to foreign youth cultures. In 1957, Moscow hosted the International Youth Festival, which brought delegations from across the world, who introduced new ideas, new clothing trends, and cross-border romance to some Soviet youth. As open as it was at the time, rock-n'-roll records remained underground. In the same period, Khrushchev tried to revive 1930s-style youth militancy by dispatching Komsomol members to tackle extraordinary projects while declaring "the Moral Code of the Builders of Communism." This set of commandments called for honesty, self-improvement, and collective spirit, all necessary to ensure that the young people of 1960 were ready to lead society to the communist future promised for 1980. In fact, this was perhaps the last burst of idealism. By the 1960s, membership in the Pioneers and Komsomol was largely compulsory and automatic, rather than an honor to be earned. By the 1980s, youth as a whole found little of interest in official curricula and ideological nostrums, and began to seek their own answers. After Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms overturned old certainties, the path to power no longer led to the Communist Party hierarchy. Ambitious and well-connected young Komsomol officials were well-placed to seize the opportunities in the emerging market economy. Indeed, some of the great oligarch fortunes of post-Soviet Russia and other successor states began with Komsomol leaders before 1991. Far from a Communist vanguard, the Komsomol organization became a spear point of capitalist penetration.

Suggested Reading and Resources

Jeffrey Brooks, Thank You, Comrade Stalin! Soviet Public Culture from Revolution to Cold War (Princeton University Press, 2000).

Juliane Furst, Stalin's Last Generation: Soviet Post-War Youth and the Emergence of Mature Socialism (Oxford University Press, 2010).

Playing Soviet: The Visual Languages of Early Soviet Children's Books, 1917--1953 http://commons.princeton.edu/soviet/.

Donald J. Raleigh, Soviet Baby Boomers: An Oral History of Russia's Cold War Generation (Oxford University Press, 2011).

![PP 525: VLKSM [All-Union Lenin Communist Union Of Youth]

Do not think that all songs have been sung,

that all thunderstorms have finished --

Prepare yourself for the great goal,

and glory will find you!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-525/pp525-200x297.jpg)

![PP 573: What is Komsomol? To teach and to learn, to raise a young generation to be loyal to the tasks of the motherland!

[On right in red box]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-573/pp573-200x133.jpg)

![PP 897: To New Successes, Young Builders of Communism!

[Quote on poster reads]:](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-897/pp-897-catalog-image-200x122.jpg)

![PP 918: Komsomols and young people! Fight diligently to increase the cotton yields! That with you [it] will make a great contribution to the battle for peace!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-918/pp-918-catalog-image-200x132.jpg)