Women

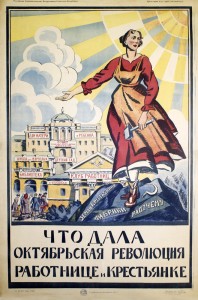

In 1917 while serving as People's Commissar for Social Welfare in Soviet Russia's revolutionary government, Aleksandra Kollontai became the world's first women to hold a government ministerial post. Her position demonstrated how the Soviet Union was offering women unmatched freedoms. In fact, the new Soviet state simplified marriage, enabled divorce, and became the first country to legalize abortion. However, cultural norms continued to limit the effects of legal equality, while state policy prioritized industrial development over concerns about "the woman question." [Text continues at bottom of page]

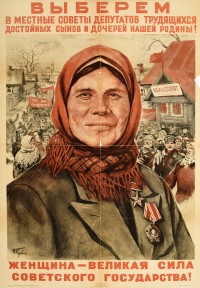

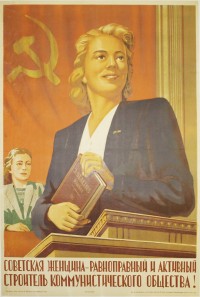

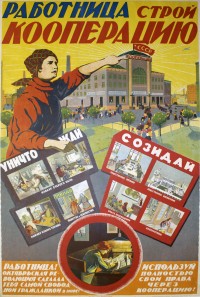

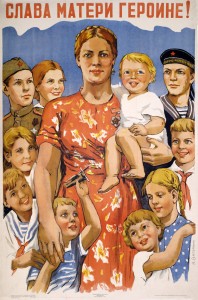

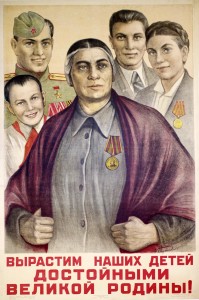

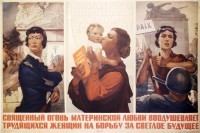

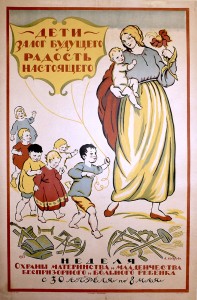

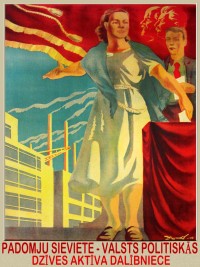

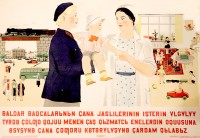

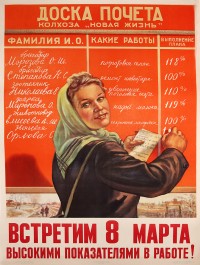

Decade after decade, women in the Soviet Union overcame difficult circumstances, including local circumstances, that belied official claims that "the woman question" had been solved by 1930. In the late 1920s, for example, communist activists viewed women as a surrogate for the working class in Central Asia, a region with few industrial workers. Seeking to consolidate a weak position, the activists challenged local Muslim cultures by recruiting women to overturn the practice of veiling, which they viewed as emblematic of society's repressiveness and misogyny. Visual and print propaganda depicted women as extraordinarily productive farmers and as contributors in metalworking, aircraft, the government, and other traditionally male spheres, although these presented idealized images of the world as it should and someday would be, rather than as it was at that time.

By the mid-1930s, Soviet authorities shifted course and promoted relatively conservative ideas about gender relations. In 1936, the government banned abortion amid fears that declining birth rates would harm economic growth and military preparedness. Although the government promised to subsidize food, housing, and childcare, such communal services remained rare. From 1941 to 1945, the Soviet Union's catastrophic experiences of World War II drastically altered women's lives. Challenging the conservatism of the late 1930s, women worked on the home front in factories and filled leadership roles. In the military, women served not only as secretaries and nurses, as in other countries, but also as combat pilots, machine-gunners, snipers, and in many other front-line posts. The postwar years reinforced old gender norms, but women remembered different times, even as they confronted the shortage of marriageable men and patched up families struck by wartime loss.

By the late 1940s, new patterns emerged alongside the old ones. As an increasingly urbanized society, the Soviet Union suffered a labor shortage and, therefore, tried to further increase women's participation in the labor force. The government again designated communal dining, laundry, and childcare to facilitate wage labor outside the home, but comparatively few women had access to the services. Women balanced jobs with cooking and housekeeping duties, but did not benefit from laborsaving devices or help from husbands, as society expected men to do little work in the home. By the mid--1950s, women held industrial occupations more often than in capitalist countries. They dominated teaching, medicine, as well as a host of professions, which held little prestige.

In 1956, the government re-legalized abortion on safety grounds, even though it continued to declare the procedure potentially dangerous to the health of women, families, and societies. Because it remained a woman's primary family-planning option, abortion carried comparatively little stigma. However, Soviet society infrequently discussed women, their bodies, and sexuality. In 1987, for example, a women speaking to an international audience, was able to earnestly declare, "We have no sex here," meaning simply that one did not discuss it in public. By the 1990s, the restraint on public discussion and display of sexuality was disappearing, often scandalizing those Soviet citizens brought up under the codes of morality. Amid the expanding possibilities for public discourse and the fundamental political and economic changes in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Soviet Union's achievements in education and healthcare---which aided women---began to erode. By the time the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, women found their circumstances profoundly changed as Russia and other former-Soviet states moved into an era of independence and sociopolitical uncertainty.

Suggested reading and resources:

Atwood, Lynne. Creating the New Soviet Women: Women's Magazines as Engineers of Female Identity, 1922-53 (St. Martin's, 1999).

Natalia Baranskaia. "A Week Like Any Other Week," Massachusetts Review 15 (Autumn 1974), 657--703.

Victoria E. Bonnell. Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters under Lenin and Stalin (University of California Press, 1998).

Mary Buckley. Perestroika and Soviet Women (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

Wendy Goldman. Women, the State and Revolution: Soviet Family Policy and Social Life, 1917-1936 (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Melanie Ilic, Susan E. Reid, and Lynne Attwood, eds. Women in the Khrushchev Era (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

Marianne Kamp. The New Woman in Uzbekistan: Islam, Modernity, and Unveiling under Communism (University of Washington Press, 2006).

Douglas Northrop. Veiled Empire: Gender and Power in Stalinist Central Asia (Cornell University Press, 2003).

Elizabeth A. Wood. The Baba and the Comrade: Gender and Politics in Revolutionary Russia (Indiana University Press, 1997).

![PP 130: Women Workers Elect Delegates!

Delegate meetings will teach you how to rule the state.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-130/pp-130-re-shoot-4019-200x284.jpg)

![PP 251: Greetings for [International Women’s Day] the 8th of March](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-251/pp251-198x300.jpg)

![PP 339: March 8th [International Women's Day], a day of celebration of the fighting forces of the working women and peasants of all countries.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-339/pp339-200x300.jpg)

![PP 431: Women Workers and Women Peasants!

Go for cooperation.

Fulfill the precept of Il’iich [Lenin] Strengthen Cooperation!

Cooperation is the way to liberation for women workers and women peasants.

The properly oriented woman worker and woman peasant should be a member of a cooperative.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-431/pp431-182x300.jpg)

![PP 655: Let’s mark International Women’s Day with victories in agricultural mastery! Woman collective farmer! Under the banner of the VKP(b) and Lenin’s Central Committee, forward to new victories. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-655/pp655-200x150.jpg)

![PP 1101: "Special attention will be devoted to organizations [providing] cultural and domestic services to young women, to care for the improvement in the functioning of kindergartens and daycares, and to create for young women workers all circumstances needed for study, development, and promotion."](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1101/pp1101-200x132.jpg)