Revolution

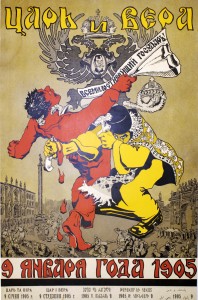

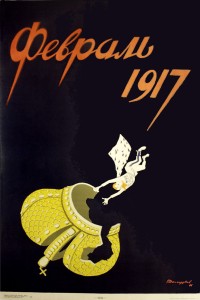

Of the many upheavals shaking Russia in 1917, the revolutions of February and October in the capital, Petrograd, proved to be decisive. As World War I dragged through its third year, discontent with the rule of the Romanov dynasty grew, compounded by mounting losses and deteriorating food supplies. In early 1917, strikes rocked Petrograd. On March 8 (February 23, o.s.), groups of women walked off the job, their numbers soon swelling to hundreds of thousands of their compatriots. Within a week, soldiers of the city garrison had refused orders to disperse the crowds, going over to the strikers' side. [Text continues at bottom of page]

As elite support drained away, Tsar Nicholas II agreed to abdicate, initially thinking to name Alexei, his 13 year-old hemophiliac son, to reign while his uncle, Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich, was to be regent. Pressed by his generals, Nicholas abdicated also in his son's name, leaving Mikhail Alexandrovich to himself refuse the throne for lack of elite support or popular backing. Amid the civil disorder, the Duma, or imperial parliament, acted independently to form the Provisional Government, quickly pledging to continue fighting the war. Yet from the beginning, it had to contend with a situation described of "dual power" because it vied with the popularly elected Petrograd soviet, or council, in which radical parties, workers, and soldiers were represented.

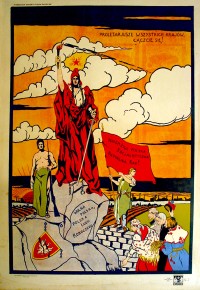

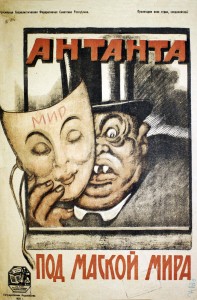

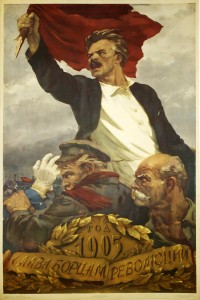

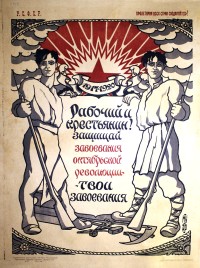

A party of Marxist revolutionaries led by Vladimir Lenin, the Bolsheviks campaigned for land reform, popular sovereignty in the form of the soviets, and an immediate end to World War I. From April through the summer and into the autumn, the party amassed the support of workers, disaffected soldiers, and radical intellectuals. Spontaneous unrest in early July encouraged the Provisional Government to suppress the Bolsheviks. In September, the party was re-legitimized when they used their influence among workers and soldiers to mobilize forces to thwart an attempted counterrevolutionary military coup, which the Provisional Government had been simultaneously complicit in encouraging but powerless to stop when it spun out of control.

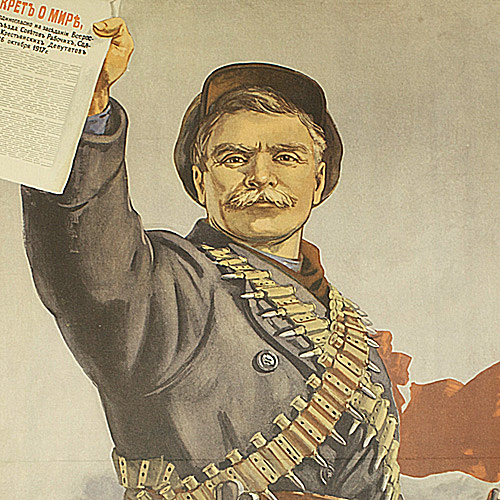

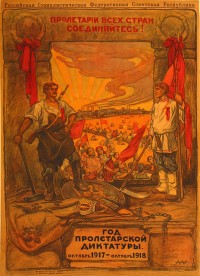

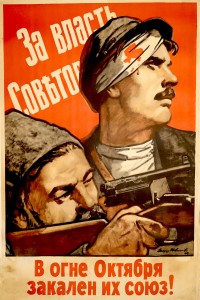

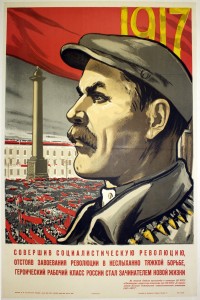

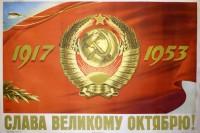

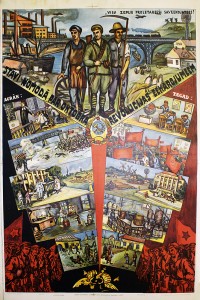

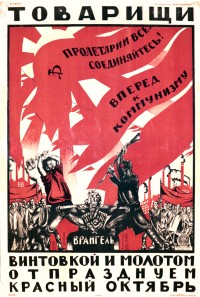

The revolution of October 25 (November 7, o.s.) witnessed armed militias loyal to the Bolsheviks overthrow the Provisional Government. The Bolsheviks seized power in the name of the soviets and established a new executive, the Council of People's Commissars, headed by Lenin. It immediately issued decrees calling for peace, land, and popular power. Calling their government a "dictatorship of the proletariat," the Bolsheviks realized their pledges by discriminating against former imperial elites, the aristocrats, and the capitalists. Although popular in Petrograd, the seizure of power paved the way for the savage Russian Civil War to follow. Emerging battered but victorious by 1922, the Bolsheviks led the formation of the Soviet Union.

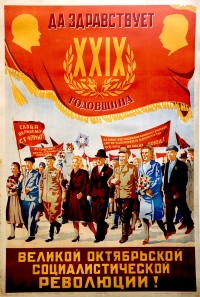

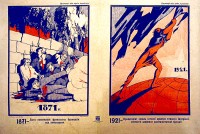

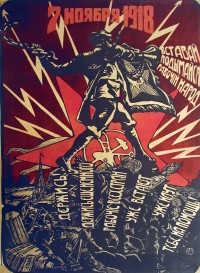

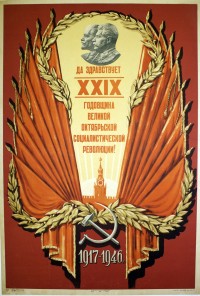

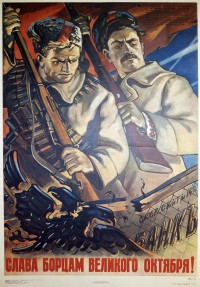

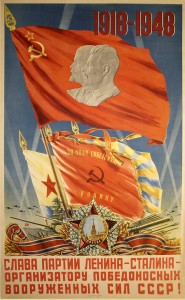

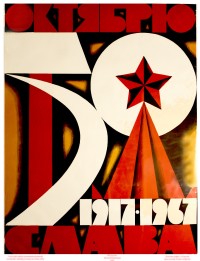

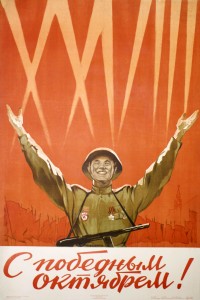

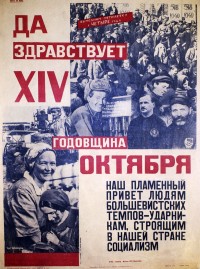

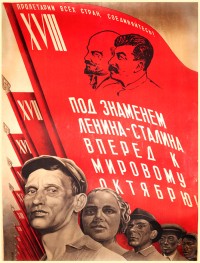

In later years, the October Revolution became the focal point for celebration in the Soviet Union, making its anniversary a red-letter day on the Soviet calendar. As early as November 7, 1918, the Communist Party staged dramatic festivals. In 1928, Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein immortalized the events of October in film, reenacting---and embellishing---the storming of the Winter Palace. Represented in literature, the fine arts, museums, theater productions, movies, monuments, and print propaganda, the defining events and personages of the revolution formed the foundations of a sense of self that bound the Soviet Union and Communist Party together.

Suggested Reading and Resources

Laura Engelstein, Russia in Flames: War, Revolution, Civil War, 1914--1921 (Oxford University Press, 2017).

China Miéville, October: The Story of the Russian Revolution (Verso, 2017)

Alexander Rabinowich, The Bolsheviks Come to Power (Indiana University Press, 1976)

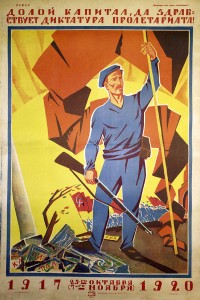

![PP 042: October 25, 1917 -- November 7, 1920

Farmer, you used to work for a landlord!

Now the land belongs to the working people!

All Power to the Soviets!

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-042/pp042-190x300.jpg)

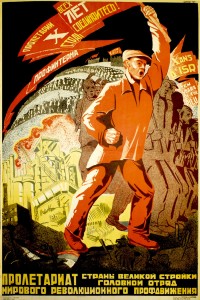

![PP 132: [Upper panel] RSFSR (Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic) Workers of all Countries, Unite!

[Lower panel] Workers of all Countries, Unite!

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-132/pp132-200x300.jpg)

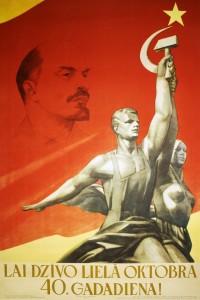

![PP 305: October

1917-1920

Comrade! Triple your energy, through mortars, bristling bayonets!

We celebrate the third anniversary of the October Revolution happily in bloody battle!

[partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-305/pp305-200x300.jpg)

![PP 322: Death to the stranglers and oppressors of workers and peasants!

Battle for the Volga [and] Battle for bread for the starving!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-322/pp322-200x135.jpg)

![PP 401: On the main square some days ago were three aces –a landlord without land, a manufacturer without a factory, a bank predator sitting without income – they were looking around for an hour. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-401/pp401-200x133.jpg)

![PP 402: [Top panel]

Away With Evil-Doers!

[Bottom panel]

Come with us!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-402/pp402-200x275.jpg)

![PP 460: Under the rule of the Party let’s fulfill the next five-year plan, improve the level of life, strengthen defense.

Sixteenth Anniversary [of] October](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-460/pp460-200x300.jpg)

![PP 470: [Top text] Fourth Anniversary of the October Revolution

[Lower left panel]

Four Years!

The end of enmity and rage

in the Republic of Labor

the worker and the grain-grower

are in unity forever.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-470/pp470-200x275.jpg)

![PP 530: 48th [anniversary of ] October](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-530/pp530-200x300.jpg)

![PP 1021: The worldwide October [Revolution] will destroy the prison-houses of the bourgeoisie!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1021/pp1021-200x149.jpg)

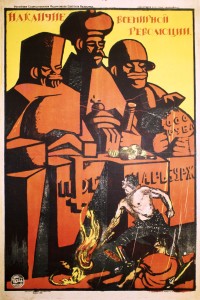

![PP 1175: How landowners and capitalists straightened out the revolutionary outlying peasantry.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1175/pp-1175-catalog-image-200x263.jpg)