International

Since its founding, the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party---and its later Bolshevik and Menshevik factions---had been members of the Socialist International, also called the Second International, an organization of social-democratic, labor-oriented political parties. When World War I broke out, socialist parties in each warring country set aside their internationalism and supported the war effort. Dissenters, including the Bolshevik's leader Vladimir Lenin, condemned the war. [Text continues at bottom of page]

Failure of the Second International enabled the Bolsheviks in 1919 to found the Third-Communist-International, or Comintern, attracting left-wing splinters from the world's socialist parties. Until 1921, the firebrand Comintern line called for transforming the chaos wartime Europe into Soviet-style revolution. Appealing to peoples subjugated in European overseas empires, the organization attracted a generation of leaders who came to power in the post-World War II era like Ho Chi Minh, future leader of North Vietnam. Desperately defending themselves in the Russian Civil War, the Bolsheviks eagerly awaited any sign of revolution in the capitalist societies, hoping that friendly new states would render aid. Although unrest flared in Central Europe, the short-lived radical republics of Budapest, Munich, and elsewhere soon fell to liberal governments and right-wing paramilitaries. As far away as the United States, red scares stamped out burgeoning radicalism and trade-union militancy.

During the early 1920s, the Bolsheviks followed two seemingly contradictory foreign policies. The Soviet Union had a traditional diplomatic corps, the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs. It signed the Treaty of Rapallo with Germany, binding the two states to challenge the international system established by the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Simultaneously, the Comintern encouraged loyal parties, such as the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), to prepare for insurrection if the opportunity arose. Indeed, a few abortive actions were planned. As Josef Stalin centralized his power in the mid--1920s under the slogan "Socialism in One Country," the Comintern shifted from preparing for world revolution to defending the Soviet Union. The policy was met with stunning setbacks. Relations with Great Britain had gradually improved via a 1921 commercial treaty and diplomatic recognition in 1924. In March 1927, a British intelligence raid on the Soviet trade authority in London revealed espionage. Britain's Conservative government severed ties with Moscow, sparking fear there that war might follow. In April, the Comintern strategy of backing the nationalist party in the Chinese Civil War while encouraging communists to work within it collapsed. An outwardly friendly new leader, Gen. Chiang Kai-shek, purged and executed communists by the hundreds of thousands, leaving Comintern policy in shambles.

As capitalist economies slid into the Great Depression, the Comintern ordered affiliated parties to dismiss the rising fascists and concentrate on the greater enemy, the socialists, who competed for the loyalty of the working class. In Germany, division on the left made Adolf Hitler's seizure of dictatorial power in 1933 achievable. Hesitating to deploy their forces, the KPD leaders were arrested or exiled and their outmaneuvered party banned and dispersed. Reeling, the Comintern reversed course to work with socialists and liberals in antifascist coalitions known as the Popular Front. In 1936, Popular Front coalitions won elections in the Republic of Spain, triggering the Spanish Civil War. While the French, British, and United States governments refused to assist the loyalist republicans, Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini supported the military rebellion of Gen. Francisco Franco and his fascist troops. Responding, the Comintern recruited volunteers from across the world to serve in the International Brigades. Stalin sent tanks, planes, and officers, but also secret police agents to enforce his political demands. Wary of alarming Western liberal governments with whom he hoped to ally against Germany, Stalin ordered the agents to persecute, imprison, and execute as traitors the leaders of non-Comintern left-wing groups.

In September 1938, the British and French leaders met with Hitler in Munich to bargain away Czechoslovakia's sovereignty. Responding, Stalin reversed course, signing the August 1939 non-aggression pact with Hitler. As Comintern policy lurched wildly in accordance with Stalin's decisions, it lost credibility and, furthermore, its leaders in Moscow fell victim to the Great Terror. In deference to wartime allies, Stalin closed down the Comintern in May 1943.

The Soviet Union achieved its greatest power and prestige during and after World War II. Its enormous wartime sacrifices earned goodwill for international communism. In France, Italy, and elsewhere, communists contributed to the underground resistance to Nazi occupation. After the war, the parties parlayed the resulting recognition---augmented by propaganda---into electoral successes. Support peaked in 1945 and 1946, and while the Communist Parties of Italy and France remained fixtures in the postwar political scene, they had to demonstrate unwavering devotion to Moscow's line. Thus, they were harmed by Premier Nikita Khrushchev's revelations about the cult and political crimes of Stalin, the 1956 invasion of Hungary, and that of Czechoslovakia in 1968, all of which robbed the Soviet Union of legitimacy. Elsewhere, communist parties failed to regroup after the war due to state repression: red scares in the United States hounded present and past members, while the Communist Party in West Germany was banned for over a decade after 1956. Amid waves of postwar decolonization, the Soviet Union attracted interest from emerging national leaders in Asia, Africa and Latin America, many of whom remembered the Comintern's anticolonial stance. The Soviet Union wooed leaders such as Cuba's Fidel Castro in hopes of forging military and political alliances. In these years, however, the Soviet Union competed with communist China for influence in left-wing circles in these regions, a sign of the increasingly strained relationship between the two, which broke for good after 1960.

Suggested Reading and Resources

Jeremy Agnew and Kevin McDermott, The Comintern: A History of International Communism from Lenin to Stalin (Palgrave, 1996).

Brigitte Studer, The Transnational World of the Cominternians (Springer, 2015).

Seventeen Moments in Soviet History, "International," http://soviethistory.msu.edu/theme/international/.

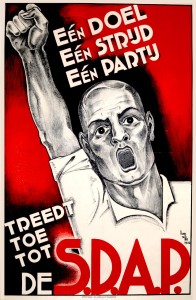

![PP 115: August 1st Demonstration.

Liberate [André] Marty and all our imprisoned men.

Down with the Fascist Social Insurance law.

United Front of the Exploited Against the Imperialist War.

Por Defense of the USSR.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-115/pp115-200x300.jpg)

![PP 400: Full legislative elections beginning Sunday December 12th, 1926

S.F.I.C. [*Societé Francaise Internationale Communiste*]

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-400/pp400-200x300.jpg)

![PP 539: Peace, Friendship and Economic Exchanges with the USSR.

Monumental construction projects are opening a future of prosperity for the Soviet people.

For work and prosperity of Italy: make economic exchanges with the USSR.

Grain and raw materials in exchange for our agricultural and industrial products.

[Text center left] USSR Wants Peace and Works For Peace.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-539/pp539-200x133.jpg)

![PP 560: You, Worker!

You must vote for your party class, the Communist Party.

[Names on right side] Candidates of the working class.

[Lower bottom] Argentinean Section of the Communist International. United States 1828.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-560/pp560-200x300.jpg)

![PP 659: Mao Tse-tung. [Pending translation (Без Перевода)]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-659/pp659-200x260.jpg)