Events

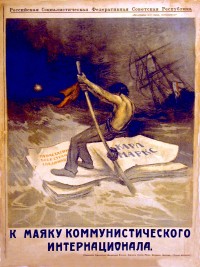

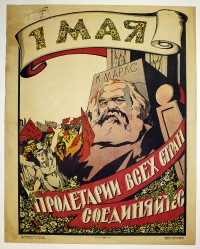

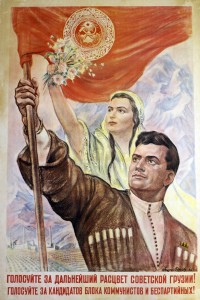

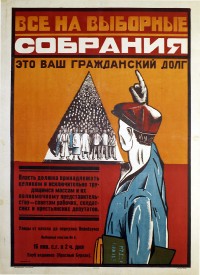

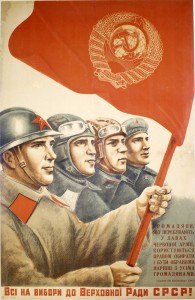

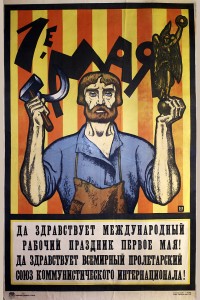

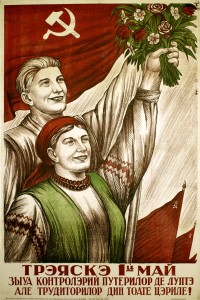

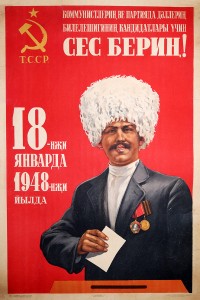

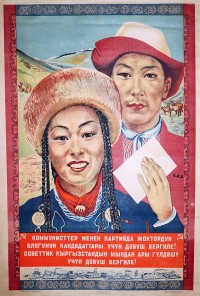

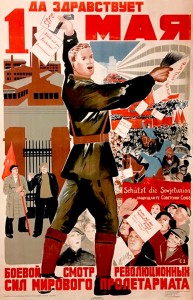

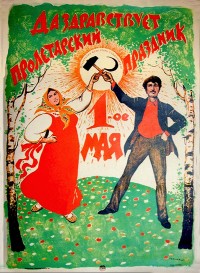

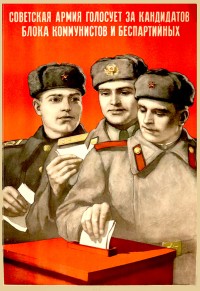

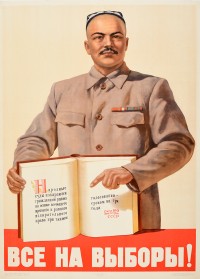

Life in the Soviet Union has been portrayed as grim and gray. While there was some truth in this impression, life was also punctuated by frequent celebrations infused with ideology and propaganda. In 1917, the Bolsheviks tried to overcome desperation and poverty by displaying fervor for the revolution and the new state's commitment to transforming society. For example, the holiday of the workers was held on May 1, 1918 and subsequently thereafter, Soviet Russia held the celebration almost every year. Cultural figures staged parades, grand public displays, and performances to encourage revolutionary ideas and nearly every event was tied to a symbol such as the red banner and "The Internationale," the socialist anthem. One key socialist holiday in the Soviet Union was the anniversary of the October Revolution that was held on November 7. The anniversary was a hallmark event until 1991 when no official celebration was organized. [Text continues at bottom of page]

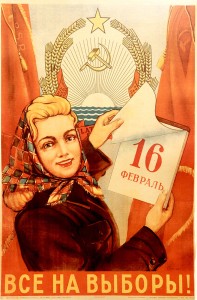

After the revolution, the new Soviet state began to discard old public events along with Imperial and religious holidays. Alternatives were conceived so new events would be uniquely socialist in content. Many latter practices, such as the attempt to replace the Christian-based christening with "Octobering" fell by the wayside while other Soviet-centeric events proved long-lasting.

Soviet Russia disestablished the Russian Orthodox Church as a power center and also officially rejected religion and any of its associated holidays. In 1917 for example, marriage was transformed from a religious ceremony into a simple act of civil registration with a few secular rituals added to the ceremony as time progressed. By the 1930s, increasing prosperity encouraged the reemergence of the Christmas tree, although it was rebranded as a way to celebrate New Year's Eve.

By the 1960s, a new central event was entered the calendar: Victory Day. Celebrated on May 9, the day commemorated the sacrifices of World War II by honoring its veterans. Initially a somber commemoration, Victory Day became a celebratory event highlighted by its enormous military parades. Combined with International Labor Day on May 1, Victory Day helped to inaugurate the spring, much like Easter for the religious. Celebration of International Women's Day on March 8 proved to be popular and it typically was accompanied by the giving of flowers and other small gifts. In parallel, there was a male-dominated celebration on February 23-- the commemoration of the founding of the Red Army. Moreover, there were special days to honor professions and bodies. Although not official state holidays requiring time off work, the days would be cause for celebration for those connected to an industry or a branch of the armed services: cosmonauts were celebrated on April 12, the anniversary of Yuri Gagarin's inaugural space flight, while active and retired paratroopers reveled on August 2.

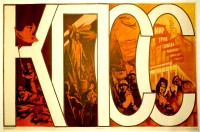

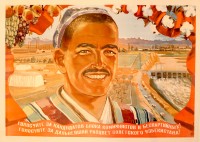

In addition to annual and semi-annual events, life in the Soviet Union included irregular events marking the lives of people buttressed with propaganda campaigns. Communist Party Congresses naturally called for party members' attention, but also influenced the lives of everyone. Held almost annually in the 1920s, they decreased in frequency under Stalin, who allowed a gap of thirteen years between 1939 and 1952 before calling another congress. His successors held them at regular intervals, approximately every four years. Mass media campaigns informed the public of new party initiatives announced at the congress, but also encouraged them to fulfill and overfill plans in the workplace "in honor of" the approaching congress or other event.

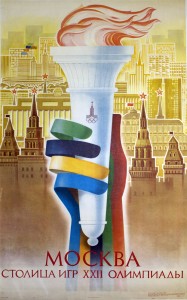

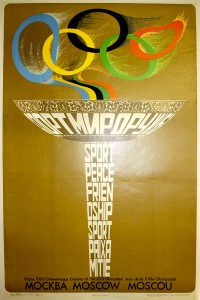

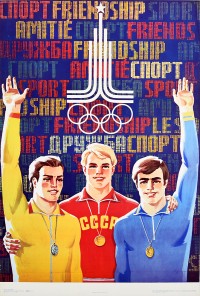

The Soviet Union irregularly hosted cultural and artistic events. International film festivals attracted foreign observers and brought global exposure to Soviet filmmakers. The 1957 World Youth Festival brought youth contingents to Moscow from far and wide, including the United States, for an event of cultural exchange that spilled over into exchanges of popular culture and some romantic relations. One-time events loomed large in the minds of those who experienced them. In 1937, the Soviet Union lavishly marked the centenary of the tragic death of the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin. Ceremonies raised the already deeply revered poet to cult-like adulation. In the postwar era, the Soviet Union entered into international sporting competition for the first time. Having previously maintained a skeptical attitude toward international organized sports competition, the Soviet Union jumped into the Olympic Games in 1952 in part to prove that communism could also compete with the capitalist opponent in this arena. The games proved a success for Soviet athletes, who trained like professionals in an era when the Olympic movement retained its amateur ethos. Bringing home a haul of Olympic medals, they sparked a Cold War competition in the sporting world. Soviet leaders viewed the 1980 games hosted in Moscow as a capstone, designed to demonstrate peaceful development and the superiority of Soviet athleticism. They ultimately suffered when the United States protested the Soviet Union's involvement in the Afghan War, leading a boycott that reduced the number of participating nations from 120 to 81.

Suggested Reading and Resources

Malte Rolf, Soviet Mass Festivals: 1917-1991. (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013).

Jeffrey Brooks, Thank You, Comrade Stalin! Soviet Public Culture from Revolution to Cold War (Princeton University Press, 2000).

Choi Chatterjee, Celebrating Women:Gender, Festival Culture, and Bolshevik Ideology, 1910--1939 (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2002).

Karen Petrone, Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades: Celebrations in the Time of Stalin (Indiana University Press, 2000).

Richard Stites, Russian Popular Culture: Entertainment and Society since 1900 (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

Richard Stites, Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution

(Oxford University Press, 1989).

![PP 056: May 1 [Karl Marx wrote] "Workers have nothing to lose but they have the whole world to gain".](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-056/pp056-200x300.jpg)

![PP 098: The 20th congress of the communist party of the Soviet Union [KPSS]

Beyond the plan.

Let's present our labor achievements!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-098/pp098-200x300.jpg)

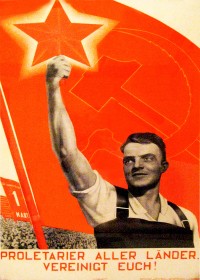

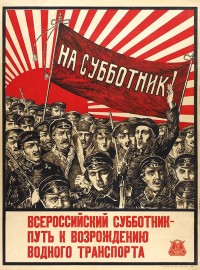

![PP 105: May 1st All-Russian Subbotnik

[Top of poster] Russian Socialist Federation of the Soviet Republic.

Workers Of All Countries Unite!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-105/pp105-200x300.jpg)

![PP 351: May 1st. Workers of all countries, unite!

[On] May 1 there will be a fighting review of the revolutionary forces of the international proletariat.

(Bottom quote)](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-351/pp351-194x300.jpg)

![PP 395: Task Number One was established at the 16th Congress of the VKP(B) to create a second coal-metallurgy industrial zone.

[Top photo of Stalin, at left] “In the course of the newest growth of our economy it has happened that the coal-metallurgy zone (in Ukraine) has become insufficient for us. What is new is that while developing this zone in different ways in the future, we must start immediately a second coal-metallurgy zone. This zone should be the Ural-Kuznetsk Plant….” -From Comrade Stalin’s speech at the 16th Congress of the Party. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-395/pp395-200x293.jpg)

![PP 537: [Pending translation (Без Перевода)]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-537/pp537-195x300.jpg)

![PP 607: [Pending translation (Без Перевода)]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-607/pp607-186x300.jpg)

![PP 722: May 1st.

Old waver of victory banners,

faithful signalman of all the poor,

locksmith of the fiery keys

to the

world-wide doors of the commune,

a grandfather of freedom, forever young,

a forger of battle-ready swords.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-722/pp-772-catalog-image-200x279.jpg)

![PP 723: Postage Stamps for Collections, for sale here [partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-723/pp723-200x300.jpg)

![PP 737: Long Live Stalin’s Constitution!

[Quote in middle] “It’s pleasing and joyful to know what our people fought for and how they achieved a victory of historical significance for the whole world.” --J. Stalin.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-737/pp737-200x278.jpg)

![PP 939: Long Live the 28th Anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution!

The end of the war! The fascists from Berlin and their allies from the East – the samurai [and]

the brave divisions of the titan-like people, who went forth, proudly defending the homeland.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-939/pp-939-catalog-image-200x300.jpg)

![PP 957: May 1, 1921

Exhibition of the Petrograd Provincе Department of Education [in the]

Building of the Great Stock Exchange, No. 1 Tuchkov Embankment.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-957/pp-957-catalog-image-200x130.jpg)

![PP 997: Twenty-second Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union [CPSU]: From Socialism to Communism

.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-997/pp997-200x127.jpg)

![PP 1031: The All-Union Population Census Begins on January 15, 1959

It is every citizen’s duty to complete the census and give accurate answers to all questions on the census form.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1031/pp1031-200x136.jpg)

![PP 1052: [Pending translation (Без Перевода)]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1052/pp1052-200x265.jpg)

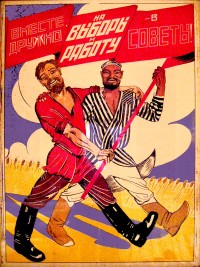

![PP 1118: Do not forget [from] March 25 to April 6

Elections to the Soviet - Show your strength

Red Moscow.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1118/pp-1118-catalog-image-178x300.jpg)

![PP 1128: Constitution of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Section I: General provisions; Section II: On the structure of Soviet Power, Organs of central government; Section III. On Voting Rights; Section IV. On the Budget of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic; Section V. On the Seal, Flag, and Capital of the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1128/pp-1128-catalog-image-200x137.jpg)

![PP 1141: Drive out the kulaks – Elect poor and middle peasants to the councils.

[Panel 1 reads]:](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1141/pp-1141-catalog-image-200x159.jpg)