Civil War

For Russia, the Civil War was the climax of a disastrous era begun by World War I and the Russian Revolution of 1917. Spurred by popular support gained by Vladimir Lenin's slogan "All power to the soviets!" and his opposition to continuing to fight World War I, the Bolsheviks seized power in the Russian capital, Petrograd, in October 1917. The Bolsheviks overthrew the failing Provisional Government with minimal violence, but the aftermath sparked a ferocious conflict. [Text continues at bottom of page]

Headed by Lenin, the Sovnarkom (Council of People's Commissars) declared itself the defender of the exploited against their oppressors, the capitalists and aristocratic landowners.

Its initial proclamations acknowledged peasants' seizure of aristocrats' land and called for the immediate end of World War I. Hoping to claim a share of their village's land, the Russian Empire's soldiers deserted in droves to return home. Rejecting the Bolshevik peace appeal, the Germans advanced to secure food needed for their wavering home front. Rejecting proposals to declare revolutionary war against them, Lenin called for peace on any terms, which he achieved in March 1918 in a punitive treaty narrowly ratified by Sovnarkom. Lenin considered the treaty concessions irrelevant because Germany appeared ripe for a revolution promising to install a friendly socialist government, but the small uprisings there in 1919 failed.

In early 1918, the fighting inside Russia intensified. Sovnarkom could rally only a few thousand trained troops, supplemented by worker militias. Skillfully organized by leading Bolshevik Leon Trotsky, the Red Army became an effective force comprised of workers and peasants led by co-opted former imperial officers, all supervised by reliable Bolshevik commissars. Revolutionary rhetoric elevated the status of laborers above that of former elites, who were denounced as class enemies, forced to communalize their lavish homes, work menial jobs, and live on starvation rations, indignities driving many to flee into exile or join anti--Bolsheviks forces. In 1918, high-profile assassinations and an attempt on Lenin's life unleashed the Red Terror. Sovnarkom empowered the Cheka, or secret police, to interrogate and imprison, exile, or execute individuals and members of groups, such as former elites, deemed hostile to the revolution. Anti--Bolshevik forces in turn summarily executed communists and workers. All sides committed atrocities against civilians. Pogroms struck Jewish communities in the empire's western borderlands, fueled by belief that Jews, who comprised a part of Bolshevik leadership in particular, were responsible for the revolution.

The Bolsheviks fought many enemies rather than a unified opposition. In addition to the three main fronts against uncoordinated White Armies led by former Tsarist officers, the Red Army also fought local nationalists and peasant anarchists. In the Northwest, the Germans and then White forces threatened Petrograd, the birthplace of the revolution. In the North Caucasus, modern-day Ukraine, and Crimea, the Red Army fought in succession against Germans, Whites, Ukrainian nationalists, and peasant anarchists. Along the Volga River and eastward along the Trans--Siberian Railway, revolutionary forces battled White armies and contingents of Czechoslovak former prisoners of war. The Germans had withdrawn in late 1918, but they were followed by the Entente powers, who sent small detachments to port cities in half-hearted opposition to the revolutionaries. By the end of 1919, the anti--Bolshevik forces were in retreat on all fronts. Yet the crisis continued. In 1920, the forces of newly independent Poland invaded, advancing as far as Kyiv. The Red Army's counterattack fueled hopes of spreading revolution abroad, but those hopes were dashed by defeat at the gates of Warsaw. Borderland conflicts in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Siberia continued. In 1920 and 1921, peasants south of Moscow rebelled, the country faced famine, and military units that had supported the Bolsheviks in 1917 rose against Sovnarkom, which they denounced as antidemocratic and centralizing.

Soviet Russia emerged from the civil war with government control over economic activity, a militarized society, routine mass surveillance, and a callousness toward individual human lives. Bolsheviks and their enemies alike claimed that the party operated as a strict hierarchy subject to iron discipline. In reality, Lenin navigated constant infighting, political disagreements, and, in regions far from Moscow, persistent localism. Although the common worldview and practices provided by Bolshevism helped unify its forces, Sovnarkom won the civil war because it controlled the country's major cities, industries, railway network, and population centers. What they won, however, was a shattered country whose people were reduced to bartering for scarce food. By 1921, industrial production had collapsed to 20 percent of the 1913 figure. In addition to the Russian Empire's millions of casualties in World War I, the civil war killed at least a million more. Harvests shrunk, causing malnutrition accompanied by a public health crisis from breakdowns in medical care and in sanitation that fueled cholera, influenza, and other pandemic diseases. In 1921 and 1922, famine gripped the lower Volga, claiming several million victims despite foreign relief efforts. Confronted with economic collapse and rebellion, Lenin mixed repression with compromises designed to facilitate reconstruction. His New Economic Policy, or NEP, mixed state control with private initiative. However, party leaders kept in mind the violence and repression of the civil war and when the NEP faltered in 1928, Josef Stalin employed both to impose demands for grain and collectivized agriculture on the countryside for his project of crash industrialization.

Suggested Reading and Resources

Laura Engelstein, Russia in Flames: War, Revolution, Civil War, 1914--1921 (Oxford University Press, 2017).

Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 3rd ed. (Oxford University Press, 2017).

Seventeen Moments of Soviet History, [1917] (http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1917-2/)http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1917-2/and [1921] (http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1921-2/)http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1921-2/

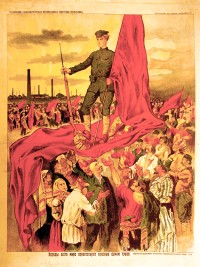

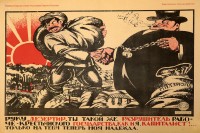

![PP 025: The first anniversary of the Red Army 1918-1919. "I am a farmer, the son of a worker, and I will be a soldier of the Red Army as long as I can hold a gun in my hands, against the hatred of the enemies of the workers." [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-025/pp025-200x261.jpg)

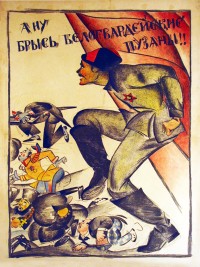

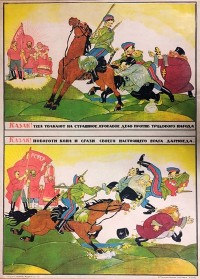

![PP 045: Farmer-Exploiter, Bandit and the Red Army.

[Poem verses]

Mitka Kunda, the company coward,

Escaped in secret from the front line,

Returned to his village, and showed up as a

Surprise guest of some of the village’s wealthy men.

The news spread through the village

That Kunda came back from the front line!

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-045/pp045-200x267.jpg)

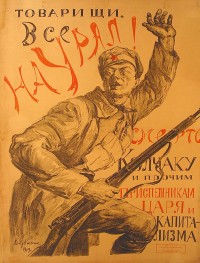

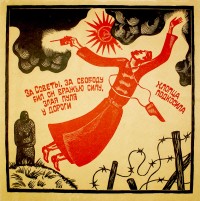

![PP 046: Comrade! Guard your right to build a political life! Guard your vote! Let not a single vote be lost! After centuries of oppression, slavery and exploitation, you are free! The political and economic power of the society is in your hands. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-046/pp046-200x269.jpg)

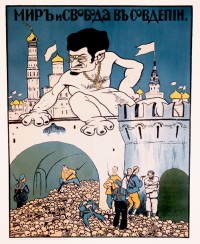

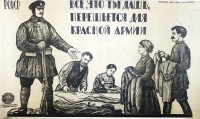

![PP 047: Universal military training [Vseobuch] is the key to victory.

Comrade! You must handle your gun as well as you handle your scythe!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-047/pp047-200x279.jpg)

![PP 143: Worker-Farmer Youth go to Officers' Command Training. Officers' Command Training gives education: basic military and political training.

Comrade Red Army Soldiers! Comrade Workers! Comrade Farmers!

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-143/pp143-200x300.jpg)

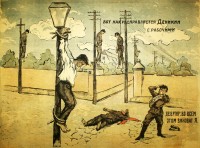

![PP 247: Kick the [Polish] Landlord out of Ukraine!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-247/pp247-200x133.jpg)

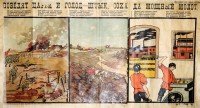

![PP 260: Did you fulfill your food donation quota?

Bad things are coming into our fatherland!

The starving Tsar is hurrying to aid Polish landlords and second-rate bastard generals who are followers of Wrangel!

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-260/pp260-187x300.jpg)

![PP 358: The work of the back line is the victory of the front line. "Our country won a victory over Wrangel not only by the courage of the Red soldiers but by the work of the Red back lines." [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-358/pp358-200x297.jpg)

![PP 417: Arise workers and slaves of the world

marked with the accursed brand

our mind has revolted and is seething

and ready to enter into mortal combat.

[From the revolutionary hymn “Arise Workers and Slaves”]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-417/pp417-200x269.jpg)

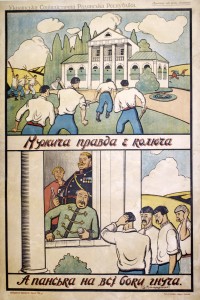

![PP 421: Poor Peasant! Citizens of Poltava will fulfill the remainder of the reduced requisition.

The Workers’ and Peasants’ Republic is placing all hope on you. You can overcome everything to fulfill requisitions sent to Poltava so city workers won’t starve. Grab the kurkul [kulak] by the neck! Let him give us the surplus he's holding back, don’t let him put his bread to rot under the earth while workers are starving!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-421/pp421-200x247.jpg)

![PP 427: [Top panel] We were successful against the tsar, we were successful against the landlords and the moneybags, we were successful against Kolchak and Denikin. [Bottom panel] How can we not be successful with steam locomotives!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-427/pp427-200x258.jpg)

![PP 428: Only the Red Army will give us bread.

[First panel] Denikin entered Kharkov, Ekaterinoslav and Moscow, Petrograd has no bread.

[Second panel] The Red Army is advancing, there is more bread in Soviet Russia.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-428/pp428-200x152.jpg)

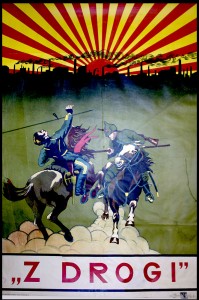

![PP 440: Curses, curses on Polish landlords!

Death and shame on perpetrators of violence!

Comrades-brothers, hurry and take up your rifles

to launch the last counter-attack against them!

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-440/pp440-200x127.jpg)

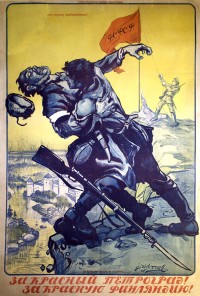

![PP 450: [At top, inside scroll] Why we need the Donetsk Basin

[Inside small scroll below just solder with red flag]

The coalfields surrounding Donetsk should be ours!

Red Army soldiers to arms! Workers and peasants to arms!

Crush the bands of the tsar's general Denikin who, for the benefit of kulaks and landlords,

wants to put to death by starvation the revolutionary peasants and workers.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-450/pp450-200x297.jpg)

![PP 563: [Let] The peasants’ crop be available to the working masses.

The Red Army protects with fortitude the will and the land of peasants.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-563/pp563-200x133.jpg)

![PP 621: The Tsar, the Priest and the Kulak.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-621/pp621-200x268.jpg)

![PP 742: The Tsar, Priest and Rich Man [are] on the Shoulders of Working People.

Three lords of the world are riding on the shoulders of workers and peasants over barren, ruined earth, over bones and bodies of dead peasants.

These three lords are the Tsar, the Priest and the greedy, insatiable, rich Capitalist.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-742/pp742-200x300.jpg)

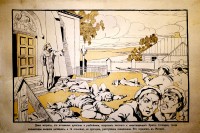

![PP 749: Why did the Civil War Start?

[In the circle] From the first days of its existence the Soviet Republic has had to stand against the military forces of the White Army.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-749/pp749-200x133.jpg)

![PP 795: Mit’ka – The Runaway.

First scene:

Brave Mit'ka the runaway,

The example of a hero,

Finally chose the time,

To run away from the front line.

Second scene:

He ran all day. Night fell.

Wind was blowing strongly.

Mit'ka would like to find

Shelter for the night.

“Auntie! I’m running from the front line…I’m so tired…”

“And where is your rifle?”

“In the snow…I lost it running!”

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-795/pp-795-catalog-image-200x259.jpg)

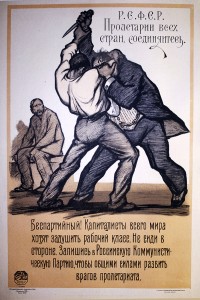

![PP 820: Priests are aiding capitalists and hindering the worker.

Get out of the way!

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-820/pp-820-catalog-image-200x135.jpg)

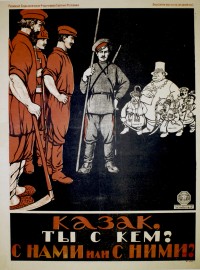

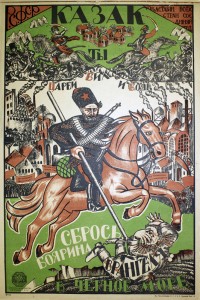

![PP 866: Cossack, Your Only Path is with Laboring Russia.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-866/pp-866-catalog-image-200x275.jpg)

![PP 867: Listen, comrade peasant! In your hands is the better future for all working people. You have the bread. The cities are now ruled by the worker, a working person the same as you. Amid the cold and the hunger, he has only one thought – to beat back all enemies [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-867/pp-867-catalog-image-200x128.jpg)

![PP 890: The Tsar, the Priest and the Kulak. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-890/pp-890-catalog-image-200x300.jpg)

![PP 893: International.

Arise, ones who are branded by the curse, A whole world of starving and enslaved!

Our outraged minds are boiling,

Ready to lead us into a fight to the death.

We will destroy this whole world of violence Down to the foundations, and then

We will build a new world.

The one who was nothing will become everything! [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-893/pp-893-catalog-image-200x300.jpg)

![PP 914: To the Aid of Pans! [Polish landlords] The Last Reserves of Marshal Foch](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-914/pp-914-catalog-image-200x300.jpg)

![PP 922: Bravely, comrades, in step!

We will strengthen our souls in the struggle,

The way to the kingdom of freedom

We will make for ourselves.

We have all emerged from the people,

Children of the family of labor!

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-922/pp-922-catalog-image-200x132.jpg)

![PP 923: Long Live the October Revolution!

Remembering Red October,... [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-923/pp923-200x236.jpg)

![PP 928: The Red Plowman.

Languishing in slavery, Red Plowman,

You were ruled by the tsars,

But you overthrow them with your powerful arms

And ventured into the field before dawn.

Applying yourself with powerful arms

And, where you poured out your blood,

Where slavery reigned for centuries,

You plow the unbroken virgin soil.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-928/pp-928-catalog-image-200x118.jpg)

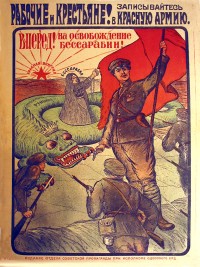

![PP 1004: Join the Ranks of the Red Army.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1004/pp1004-200x267.jpg)

![PP 1005: Tighten all forces and chop-off the counter-revolution of the remaining head.

[Alexandr] Kolchak, [Nikolai] Iudenich, [Anton] Denikin, [Simon] Petliura [are all] destroyed.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1005/pp1005-200x263.jpg)

![PP 1081: Peasant! Support the Red Army soldier with bread. He fights for you. The Red Army soldier will return to the factory and [manufacturing] plant and will make for you everything you require.](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1081/pp1081-200x135.jpg)

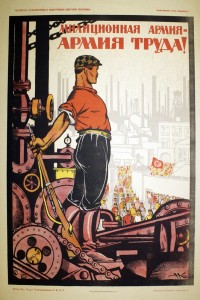

![PP 1082: Devastation and the Army of Labor.

Panel 1). The emblem of bondage has been smashed by the hand of the proletariat yet a shadow still surrounded the Soviet emblem. DEVASTATION is frightening, and with the legacies of tsarist rule, a fierce fight remains yet in front of us.

Panel 2). Its offspring are savage COLD and HUNGER, and the creeping PESTILENCE fed on us among the filth.

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1082/pp1082-200x139.jpg)

![PP 1114: A great battle is coming. A decisive battle is approaching. All of Europe is full of clamor from voices of proletarians indignant and eager to struggle. Underground shocks are coming from different parts of our planet. In a thunderstorm and storm, in blood and tears, in hunger and eternal suffering [comes] a new world, a shining world of communism, a universal brotherhood born of working people. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1114/pp-1114-catalog-image-199x300.jpg)

![PP 1122: А tale about the Cossack Erem, who was captured by the Bolsheviks. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1122/pp-1122-catalog-image-200x158.jpg)

![PP 1143: Against Redistribution!

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1143/pp-1143-catalog-image-200x153.jpg)

![PP 1172: It will not be like this anymore.

[First panel of text]: There lived a capitalist, and henchmen around him - he helped rob honest working people. The first henchman is an official. He wrote laws. According to these laws, he deftly wrote that everything was for the wealthy: land, bread, and all kinds of food, but nothing for the worker. [Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1172/pp-1172-catalog-image-200x275.jpg)

![PP 1173: Song of Labor

[Partial translation]](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1173/pp-1173-catalog-image-200x151.jpg)

![PP 1174: Comrades peasants and workers!

Protect our bread from [General] Denikin's locusts.

Remember, comrades, only with a rifle in hand will we be able to defend the harvest!](https://www.posterplakat.com/thumbs/the-collection/posters/pp-1174/pp-1174-catalog-image-200x142.jpg)